Project Description

Author: Robert Watson

rocky@rockflat.com.au

Keywords: carbon capture and storage, CO2, carbon trading, carbon offsetting, fossil fuel, mining, Chevron, Gorgon gas field, CCS

CARBON CAPTURE & STORAGE – an expensive exercise in greenwashing | 26th January 2024

The effects of climate change and global warming are now being felt world wide. Respectable science is unanimous in acknowledging climate change, recognising that anthropogenic climate change – that caused by human impact – has quickly escalated the natural climate cycles that have occurred throughout Earth’s history.

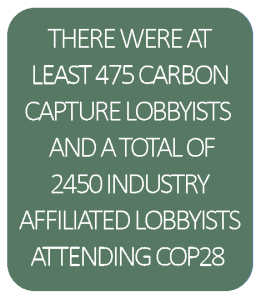

Leading into COP 28 in December 2023 there was anticipation that enough strong and influential governments were going to take the necessary steps to boost investment and activity in renewable energy technology and at the same time, initiate policies to reduce carbon emissions in the environment. However, COP 28 that started so positively, ended with a whimper as scientists and climatologists were railroaded by the business lobby and their subservient government representatives who were sent to Dubai to achieve a different outcome at this climate conference held at the historical heart of world oil production and led by the former head of Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC), Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber.

Despite the hesitancy and lack of uniform solutions to global warming by many world leaders, the interest and publicity in renewable energy projects has intensified around the world. One technology that has attracted renewed and increased attention is Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) and the related Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS) technology. Due to the influence and enthusiasm of some COP members, whose agenda was dictated by board rooms around the world, CCS became a major topic of interest and discussion at COP 28 and was endorsed by people representing interests and welfare that were elsewhere – these people should have known better. Support for CCS, despite an equivocal history, consistently poor results, and enormous expense, was very strong with one group of COP representatives whose argument for abatement of emissions fitted with their forceful push for continuation of fossil fuel mining because they make a lot of money from it. A second group at COP 28, opposed to emissions abatement, wanted more effort and financial support for renewable, clean energy sources. Strong support for CCS and continuation of fossil fuel mining at COP28 came from UAE (the hosts), Australia, Canada, Egypt, the EU, US, Japan and Denmark. Opposition to continuation of fossil fuel mining and CCS came mostly from climate-affected countries including Somalia, Niger, Guinea-Bissau, Tonga, Eritrea, Liberia and Solomon Islands – none of whom have a strong voice in the decision-making process at COP.

Despite the hesitancy and lack of uniform solutions to global warming by many world leaders, the interest and publicity in renewable energy projects has intensified around the world. One technology that has attracted renewed and increased attention is Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) and the related Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS) technology. Due to the influence and enthusiasm of some COP members, whose agenda was dictated by board rooms around the world, CCS became a major topic of interest and discussion at COP 28 and was endorsed by people representing interests and welfare that were elsewhere – these people should have known better. Support for CCS, despite an equivocal history, consistently poor results, and enormous expense, was very strong with one group of COP representatives whose argument for abatement of emissions fitted with their forceful push for continuation of fossil fuel mining because they make a lot of money from it. A second group at COP 28, opposed to emissions abatement, wanted more effort and financial support for renewable, clean energy sources. Strong support for CCS and continuation of fossil fuel mining at COP28 came from UAE (the hosts), Australia, Canada, Egypt, the EU, US, Japan and Denmark. Opposition to continuation of fossil fuel mining and CCS came mostly from climate-affected countries including Somalia, Niger, Guinea-Bissau, Tonga, Eritrea, Liberia and Solomon Islands – none of whom have a strong voice in the decision-making process at COP.

Carbon trading, carbon offsetting and Australia’s recent policy direction with the Safeguard mechanism are discussed in a Rockflat essay in 2023 (https://rockflat.com.au/portfolio-items/decarbonising-australia/). Carbon capture and storage featured in another Rockflat essay published in October 2021 (https://rockflat.com.au/portfolio-items/carbon-capture/). Because of growing support for this ineffective and very expensive procedure since that time, there is an overwhelming need to delve further into CCS and give some facts and information that would be difficult to find in regular press, and certainly not in current government releases.

A BRIEF BACKGROUND

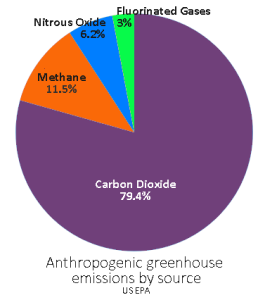

In greenhouse gas, CO2 is only part of the problem – admittedly a large part. Other greenhouse gases in significant amounts are methane, nitrous oxide, fluorinated gases and water vapour. Surprisingly, water vapour is a significant and harmful greenhouse gas and although not linked directly to human activities, the water vapour reacts with the other greenhouse gases because warmer air holds more water, and water absorbs more heat. Water vapour can also have a cooling influence as it does increase cloud cover, although the net impact from water vapour is a warming effect. Although methane (NH3) represents only 10% of greenhouse gas, it is at least 25 times more potent than CO2 at trapping heat in the atmosphere. 1 tonne of NH3 is equivalent to 25 tonnes of CO2, making it is a very effective and dangerous greenhouse gas.

In greenhouse gas, CO2 is only part of the problem – admittedly a large part. Other greenhouse gases in significant amounts are methane, nitrous oxide, fluorinated gases and water vapour. Surprisingly, water vapour is a significant and harmful greenhouse gas and although not linked directly to human activities, the water vapour reacts with the other greenhouse gases because warmer air holds more water, and water absorbs more heat. Water vapour can also have a cooling influence as it does increase cloud cover, although the net impact from water vapour is a warming effect. Although methane (NH3) represents only 10% of greenhouse gas, it is at least 25 times more potent than CO2 at trapping heat in the atmosphere. 1 tonne of NH3 is equivalent to 25 tonnes of CO2, making it is a very effective and dangerous greenhouse gas.

Earlier in the 21st Century CCS was re-discovered as a potential weapon against global warming. Between 2000 and around 2015, billions of dollars was spent on the research and attempted development of successful CCS schemes with limited success. After 2015, the main interest in CCS came from the fossil fuel industry as “big oil” sought ways to offset carbon emissions to perpetuate the business responsible for the majority of CO2 emissions. Today with business executives and governments lobbying overtly and covertly for CCS, little is being heard about technologies that will help reduce and actually eliminate CO2 emissions.

The technology of capturing carbon in the form of Carbon Dioxide (CO2) has been around since the 1920’s when CO2 was separated from the economically important methane gas, but not stored. From the 1970’s for commercial reasons, the first steps of CO2 storage began with some of the separated CO2 piped from gas reservoirs to oil fields where it was injected into the oil reservoir to assist in oil recovery. It was possible to re-capture CO2 that had already been used and re-use it until the oil reservoir was depleted. The remaining CO2 was then sealed into the rock formation that contained the oil, and as long as the host rock was sealed securely from surrounding rock formations and the atmosphere, the CO2 would remain in situ. Without an economic motive there had been little interest or effort in separating and storing CO2. CCUS has recently emerged as a related technology with the idea of using stored CO2 in agricultural and manufacturing processes. (See: https://thebulletin.org/2022/09/plagued-by-failures-carbon-capture-is-no-climate-solution/)

THE CAPTURE of CO2

There is a strong correlation between coal, oil and gas mining and enthusiastic support of carbon capture and storage technology. This correlation exists because the continued extraction of hydro-carbons as energy sources is contingent on coal, oil and gas miners finding methods to reduce CO2 in the environment – that is, the environment, not just the atmosphere. As with carbon trading, where forests and tree plantations are supposedly set aside as carbon “sinks”, carbon capture and storage and carbon storage and utilisation are simply offsetting tools. CO2 is taken from one place and stored in another. Society has to suffer the vigorous campaigns of the fossil fuel miners through press, advertising and influencing our decision makers that their market-rooted schemes actually do what they say when in fact CCS is not effective and carbon offsetting is fast evolving into yet another marketplace for business to play in. Even if the CCS process were effective there is no real reduction or removal of carbon/CO2 from the environment.

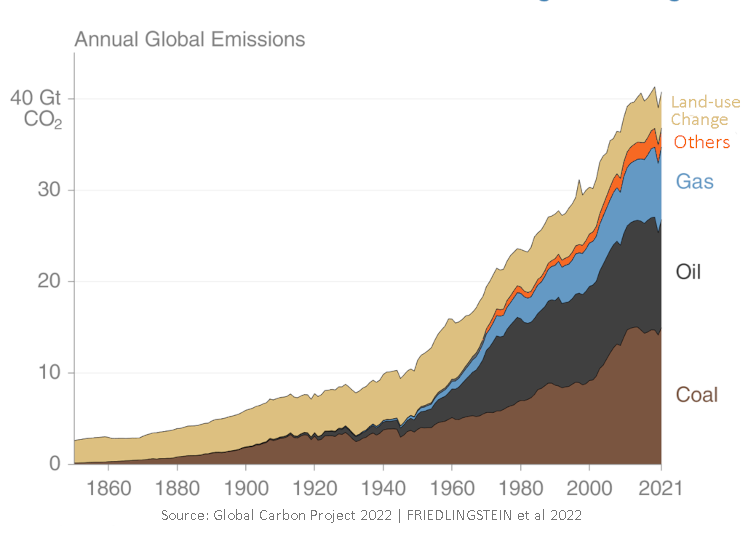

In order to ascertain the effectiveness and/or viability of different emission reduction technologies and methods, it’s important to have an idea of the amount of CO2 emissions each year worldwide. The most recent full year figures available at this time are for 2022. The following world emissions figures are from Our World in Data.

Since the transition of industry in the Industrial Revolution from approximately 1760 to 1850 a relatively flat growth curve of emissions rose from about 200 million tonnes of CO2 per annum to 6 billion tonnes in 1950. By 1990 emissions reached 22 billion tonnes per annum, and in 2022 were 34 billion tonnes. Despite attempts in recent years to reduce emissions, it is estimated that although emissions growth has slowed, they have yet to reach their peak. (ourworldindata.org)

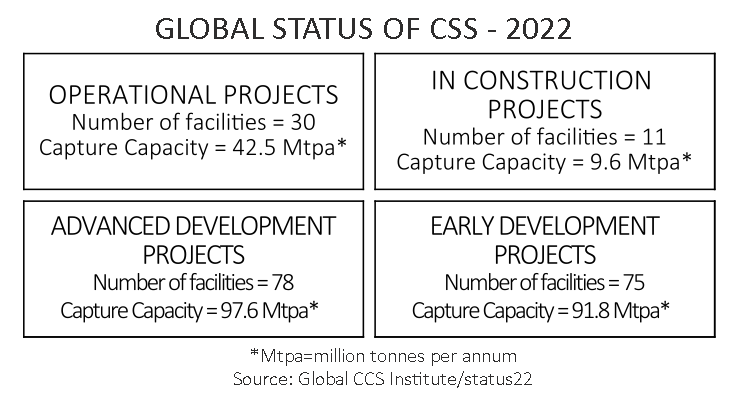

To determine the emissions reduction effect of carbon capture and storage (CCS) and the more recently renamed carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS), we need to know exactly how much carbon, and specifically CO2 is being captured, and more importantly, actually stored. Determining this figure was not as simple as determining emissions, as there are abundant estimates and views available, both for and against CCS. The figures chosen for this exercise are taken from a paper by the Global CCS Institute named “Global Status of CCS 2022” (https://status22.globalccsinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Global-Status-of-CCS-2022_Download.pdf), which had one of the more positive outlooks for CCS technology.

The Global CCS Institute uses 4 categories to differentiate between the varied status of current CCS projects active around the world. The following information is for year 2022:

Therefore a total of 194 facilities, both active and developing, will when all development is completed under ideal circumstances have a total capture capacity of 241.5 million tonnes per annum. That would be just 0.69% of total 2022 CO2 emissions! A realistic valuation of CCS/CCUS capacity based on only operational CCS projects in 2022 is that all CCS/CCUS facilities operating in the world during 2022 managed to sequester about 0.12% of emitted CO2 – a miniscule amount. (See Ad-1 in Addendum at the end)

Relating the CO2 capture figures to Australia, the worldwide total sequestered CO2 in 2022 of 45.2 million tons is slightly less than 10% of all Australia’s total CO2 emissions of 463 million tonnes in 2022 (https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions).

How is it possible to scale up CCS to a level where it actually makes a difference to CO2 levels when the process is basically still a science experiment without proven results.

THE STORAGE of CO2

The storage of sequestered CO2 is a problem that has yet to be satisfactorily overcome.

Geological storage is the ‘injection of CO2 captured from industrial processes into rock formations deep underground, thereby permanently removing it from the atmosphere’ (Source Global CSS Institute). This confident statement from a fact sheet by the Global CSS Institute belies the truth about the proposed storage strategy to be used for the majority of sequestered CO2. Proponents contend that depleted subterranean gas reservoirs or saline aquifers have been effectively storing gases and liquids for millennia. However, adequate storage options are not only relatively scarce but also not accessible in all regions where they may be required. This gives rise to an additional logistical and financial challenge: the safe transportation of CO2 from the emission point to the storage facility, a problem discussed later.

There are large areas of subterranean Earth that are unsuitable for geological storage. Newer areas of the Earth’s crust still have relatively fresh primary volcanic and igneous rock with few large sedimentary basins to make suitable reservoirs – most of Europe is in this category. Other areas that may have suitable basins or reservoirs do not have secure cap rock to ensure that stored CO2 does not escape into the atmosphere.

Despite the misplaced confidence of the fossil fuel miners there is much we don’t know about introducing large quantities of CO2 into underground storage under high to extremely high pressure exerted by the increasing mass of rock overburden into the Earth’s crust.

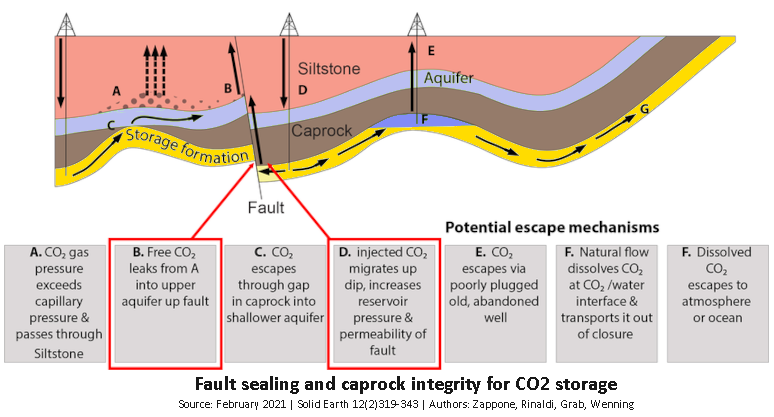

CO2 is not an inert gas and will chemically and physically react with different minerals it encounters. The CO2 will not be in a gaseous state when stored at 800 metres or more, it will be in supercritical condition in fluid state and denser than it is as a gas. In supercritical state, CO2 is more easily diffused, has a lower viscosity and lower surface tension making it easier to pump, but also making it more fluid and migratory, meaning supercritical CO2 will migrate more easily from one rock formation or reservoir to another should there be even small breaches in the cap rock, or abandoned drill holes. Moreover, CO2 is yet another “waste” product, along with the wastewater from fracking, to be disposed of by extending the pollution we’ve created in the atmosphere to pollute the subterranean area of Earth as well. The recommended storage depth of minimum 800 metres is to avoid contamination of groundwater that may become surface water, and should be made a mandatory requirement.

Ensuring secure carbon storage in geological formations depends on permanent containment for injected carbon dioxide (CO2) in the storage formation at depth. The sealing capacity of the caprock that overlies the storage formation is critical, and assessment must allow for the occurrence or presence of geological faults and fractures within the storage reservoir rock formation along which stored carbon may migrate.

The mining giant Glencore has sought approval from the Queensland government through their subsidiary Carbon Transport and Storage Corporation (CTSCo) to liquefy CO2 they hope to capture at the Millmerran power station, truck it 260km to a gas injection site near Moonie. There has been strong opposition to this proposal from an alliance that, although surprising, is becoming more common – farmers and environmentalists. The chief executive of Queensland Farmers’ Federation, Jo Sheppard, argues that any approval of this nature may open the gate for many other proponents to be looking at the Great Artesian basin for CO2 storage, endangering one of Australia’s greatest environmental assets. Sheppard said a group of the project’s opponents, including the National Farmers’ Federation, Agforce and Queensland Conservation Council, are “prepared to take it to the high court if necessary”. The argument was backed up fy National Farmers Federation (NFF) president David Jochinke who said “injecting coalmine waste into this vital water source, it puts food production at serious risk” (Guardian | Aston Brown | 9-Dec-22). Predictably an unnamed Glencore spokesperson said some claims made by agricultural bodies have been irresponsible, misleading and alarmist.

Given Glencore’s poor record with the Gorgon CSS (see Add-2 at end) facility there should be cause for concern that this company has acquired even more public funds to surreptitiously develop the case for continued fossil fuel mining with fancy websites, beautiful photos and little relevant information for the public. Apart from the potential damage to underground water that is vital for agriculture, the CO2 emitted with the building of the infrastructure for this Glencore project, the hundreds of kilometres by road transport of the CO2, and the difficult and risky process of injecting the CO2 deep underground would possibly use more CO2 than is actually going to be stored! As Polly Hemming, from Australia Institute said CCS is site specific … “If you wanted to do a pilot project for carbon capture and storage for cement production, you would attach it to a cement project. CCS is not used by the fossil fuel industry to decarbonise, it is abused as a PR and marketing tool.”

After the years and amount of money spent, including billions of dollars in government subsidies, propping up this problematical technology, one must surely question the reasoning behind it. One of the arguments in favour of CCS/CCUS is that now the hard research work has been done, the huge expense involved with CCS will start to come down in a cost curve through repetition. However, this argument does not allow that each CCS facility is bespoke, designed for the situation, geography and geology in each situation and will remain costly to build and maintain. (See Add-3 at end)

After the years and amount of money spent, including billions of dollars in government subsidies, propping up this problematical technology, one must surely question the reasoning behind it. One of the arguments in favour of CCS/CCUS is that now the hard research work has been done, the huge expense involved with CCS will start to come down in a cost curve through repetition. However, this argument does not allow that each CCS facility is bespoke, designed for the situation, geography and geology in each situation and will remain costly to build and maintain. (See Add-3 at end)

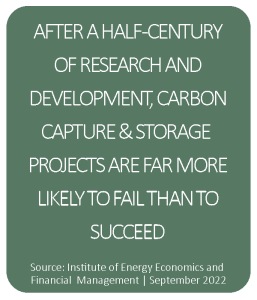

A September 2022 report by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) stated that “after a half-century of research and development, carbon capture and storage projects are far more likely to fail than to succeed, and nearly three-quarters of the carbon dioxide they manage to capture each year is sold off to fossil companies and used to extract more oil”. The analysis in the report flagged 13 major projects accounting for 55% of the world’s current carbon capture capacity in 2022. The total capture of 39 milion tonnes of CO2 per year is hardly more than one-thousandth of the 36.3 BILLION tonnes of CO2 emitted in 2021.

At COP 28 Australia’s Climate Change Minister, Chris Bowen, indicated Australia may agree to a commitment to phase out fossil fuels. Bowen’s hesitancy to wholeheartedly endorse this proposal is disappointing and reflects the situation that the fossil fuel miners are definitely in charge of climate strategy in Australia. This situation has to change and despite the hopes of many in May 2022, this current Labor government has no more influence or power of the fossil fuel industry and climate strategy than did the multiple conservative governments of the previous ten years. Balance of power with “teal-like” independents is probably the most likely way for ordinary Australians to have their say … and be listened to!

There is a need for a continued supply of coal in the short term, especially some of the specialist coal types such as the bituminous, metallurgical coal, and some brown coal. The same can be said of gas, which produces less CO2 emissions than coal and is being used as a transition fuel as the world slowly tracks towards renewable energy sources. However, in the fossil fuel industry, including extraction, processing and utilisation of fossil fuels, there is no place for carbon capture and storage(CCS). The fossil fuel industry has got behind CCS and basically used it as a fig leaf to make it look as if the emissions from their mining and processing activities are somehow being, or are going to be, offset by CCS. In order to do this just for the fossil fuel industry, the rate of CCS would need to be boosted 25 fold, and even the miners must know that is ‘pie in the sky’.

There is a need for a continued supply of coal in the short term, especially some of the specialist coal types such as the bituminous, metallurgical coal, and some brown coal. The same can be said of gas, which produces less CO2 emissions than coal and is being used as a transition fuel as the world slowly tracks towards renewable energy sources. However, in the fossil fuel industry, including extraction, processing and utilisation of fossil fuels, there is no place for carbon capture and storage(CCS). The fossil fuel industry has got behind CCS and basically used it as a fig leaf to make it look as if the emissions from their mining and processing activities are somehow being, or are going to be, offset by CCS. In order to do this just for the fossil fuel industry, the rate of CCS would need to be boosted 25 fold, and even the miners must know that is ‘pie in the sky’.

Carbon capture and storage probably has a minor role to play for some industries such as cement manufacture where there is no other option available at this stage. On past performance, and the reluctance of CCS supporters to spend the huge amounts of money that would be necessary to make CCS viable throughout all industry, a minor role is just about all that CCS technology could fill, or at least be of some assistance. (Minor use of CSS would fall into the category of “low CSS use” – see Add-3 below)

To finish, a quote from Vicki Hollub, the CEO of Occidental Petroleum, the fossil fuel colossus that has received hundreds of millions of dollars in grants from the US Department of Energy … “direct capture technology is going to be the technology that helps to preserve our industry over time. This (the grant) gives our industry a license to continue to operate for the 60, 70, 80 years that I think it’s going to be very much needed.” As Jonathon Foley remarked in an essay in Scientific American – 4th December 2023 – “Mission accomplished. Carbon capture is being used to distract the world from rapidly phasing out fossil fuels, all on the taxpayer’s dime.”

It is difficult not to conclude that carbon capture and storage is little more than greenwashing.

ADDENDUM

Add-1. Quite a number of the articles and papers read in researching this essay were positive about the carbon capture and storage process. Positive CCS views were expressed by parties with a vested interest in making CCS a success, or at least to appear successful. Not one positive CCS article written by an academic, scientist or climatologists was found. A number of press stories relating to “successful” CCS ventures quoted CO2 capture figures of millions of tonnes, which sounds impressive until the millions captured is related to the billions emitted, and nowhere in CSS supporting media were the capture vs emission figures compared. Total capture of CO2 is significantly less than 1% of CO2 emission, and there has been no significant improvement in CO2 capture for years.

Add-2. In Australia, one of the largest, most publicised and long-running carbon capture projects in the world – Chevron’s Gorgon CCS project at the Gorgon liquified natural gas plant has failed to deliver even one third of the 80% carbon capture promised when Chevron accepted millions in taxpayer subsidies to add to the $3 billion spent on Gorgon so far. One must wonder why the fossil fuel industry and some of their political supporters holds this project up as a good or successful example of CSS. It is neither!

Add-3. If arguments about the ineffectiveness of the CSS technology were not sufficient to turn people away, perhaps an analysis about the dollars involved will help.

Richard Black, an Honorary Research Fellow at the Grantham Institute, Imperial College, London has spoken on BBC Science in Action posing the question, which is less expensive in trying to achieve net zero – using lots of CCS – high CSS – to offset about 50% of emissions, or using low CSS and targeting only about 10% of emissions? On current technical costs and projecting probable changes through to 2050, the low CSS would be about a trillion dollars cheaper EACH YEAR! That would be a trillion dollars to spend on clean renewable energy technologies and sources each and every year to reach net zero.

Written by Robert Watson

Published 26th January 2024