Author: Robert Watson

rocky@rockflat.com.au

Keywords: Safeguard Mechanism, carbon offsets, carbon trading, Chubb Review, carbon capture and storage, CO2, fossil fuel, mining, Chevron, Gorgon gas field, CCS

Decarbonising Australia | 25th July 2023

With the widespread use of carbon credits, expensive

and unproven technologies, as well as new coal

mine approvals, Australia is making the difficult job

of reaching net zero by 2050 almost impossible …

Since May 2022 there have been three significant matters that will largely determine Australia’s direction on climate policy in the next few years. The first was the defeat of the Coalition government by the Anthony Albanese led Labor Party. The second matter was the reform to the Safeguard Mechanism by the new Labor government early in 2023, and the third and related matter was the Chubb Review into the Australian Carbon Credit Unit (ACCUs) scheme.

Labor’s defeat of the Liberal-National Party coalition ended ten years of neglect of the effects of climate change on Australia, and Australia’s situation and standing in the global fight against climate change. Labor’s election win wasn’t so much an overwhelming victory, rather an illustration of the public disillusionment with both major parties, but especially the Liberal-National coalition. Independent candidates, most of them broadly representing the Teal movement for more action against climate change won 10 seats, the Greens 4 seats with 2 other seats going to minor parties. The Labor government held a slim majority in it’s own right of 77 seats to 74, which improved to 78 to 73 after a post election by-election. Under these circumstances, climate policy would doubtless be more pro-active with a hung parliament relying on the ‘Teal’ votes. Independents and Greens do hold the balance of power in the Senate.

Reform of Australia’s Safeguard Mechanism1 was long overdue. The Safeguard Mechanism is the Australian Government’s policy for reducing emissions at Australia’s largest industrial facilities by setting ever-reducing limits on the greenhouse gases emitted from those facilities, it was first legislated in 2014 and has been in place since 2016. Reform of the ineffective 2016 version of the Safeguard Mechanism was a priority of the newly elected government – part of a promised and expected change in direction for Australia’s climate policy. The reformed legislation was passed early in 2023 to become effective on 1 July 2023.

The ineffectiveness of the now outdated Safeguard Mechanism of 2016 was due to the generous allowances for emissions and liberal tolerance in the options available to offset excess emissions and inadequate governance of the whole scheme by the Liberal-National Party Coalition Government that had moved from the decarbonising policies supported by the Gillard Labor Governments revised Renewable Energy Target (RET)2 to vigorous support for carbon offsetting by methods such as carbon credits and anthropocentric or simulated carbon capture and storage. A change in policy direction that not only stopped enduring carbon emissions reduction, but also diverted funds from the development of renewable energy technologies to private and semi-private carbon markets through the use of carbon offsets or ACCUs (Australian Carbon Credit Units) in Australia.

The Safeguard Mechanism (Crediting) Amendment Bill 20231 was passed by both houses of Parliament on 30 March 2023. The reforms should achieve results that would not have been possible under the original bill introduced by the Abbott Government in 2014. The tightening up of the baseline limits and setting of carbon budget and defined gross emissions caps are aimed at limiting net emissions from the 215 Safeguard Mechanism facilities to no more than 100 million tonnes in 2030 and net zero by 2050.

The Clean Energy Regulator and other connected public bodies will be required to be more transparent. There are now stricter anti-avoidance measures for businesses intending to or avoiding their Safeguard Mechanism obligations. A Greens amendment ensured the inclusion of a climate trigger to assess the impact of any new proposed projects and to block projects having more than a designated amount of emissions.

Disappointments for the climate and science communities are that the Safeguard Mechanism accounts for just 215 polluting facilities, and although these facilities are the largest emitters, there is only 28% of Australia’s total greenhouse gas emissions accounted for. However, of most concern is the use of offsetting as a means of balancing emissions. Facilities in the Safeguard Mechanism can earn trade-able Safeguard Mechanism Credits (SMCs) when their emissions are below their baseline which can then be surrendered or sold to other Safeguard facilities to help them meet their baseline obligations. One of Australia’s leading top energy economists RepuTex was engaged by Climate minister Chris Bowen to model the government policies. RepuTex advised against using free carbon crediting as a motivator since the facilities purchasing the credits might not have an incentive to lower their own emissions. That caution has gone unheeded.

After the reforms to the Safeguard Mechanism were announced, new modelling for the Climate Council and the Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) by RepuTex showed that emissions from just 16 proposed new coal and gas projects is equal to one-quarter of overall emissions reductions the revised Safeguard Mechanism aims to achieve this decade.

Dr Jennifer Rayner, Climate Council Head of Advocacy said, “If we don’t get the settings right, new coal and gas will eat a large and growing share of the Safeguard Mechanism’s emissions budget in the years ahead. Worse, if the production of coal and gas is even a little higher than the government has predicted, this risks blowing the carbon budget entirely. That’s before taking into account the more than 100 further fossil fuel projects still in the development pipeline.”

“Either this would mean Australia fails to meet our 2030 emissions reduction target, or existing facilities would have to cut their emissions by far more to make up the gap – there’s only two ways this can go. The Safeguard Mechanism settings should prioritise Australia’s critical industries to ensure this doesn’t happen.” 3

What should be of further concern for the Clean Energy Regulator is methane. There are no specific measures to account for and govern methane emissions in the Safeguard Mechanism, and there is ambiguity in the different methods for measuring methane emissions from open-cut and underground coal mines. As well as methane emissions from coal mining, only a portion of the methane emissions from the 7+ million tonnes of food waste per year in landfill is being collected.

The Chubb Review of Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs) was conducted early in 2023 after the validity and integrity of ACCUs was questioned by climate scientists, some industry bodies and independent climate organisations. The review was chaired by Professor Ian Chubb, former chief scientist, with Dr Annabelle Bennett, a retired Federal Court Judge, Ariadne Gorring, co-CEO of the Pollination Foundation, and Dr Steve Hatfield-Dodds, a philosophical economist as review panel members.

The panel examined governance arrangements and legislative requirements of the carbon crediting scheme administered by the Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF), as well as the integrity of the key methods used, and other scheme settings affecting the integrity of ACCUs.

The findings of the review are no less diverse than the personnel on the panel. The review panel concluded that the Australian carbon market is functioning as was intended but noted that there were 14 major points raised for consideration for change or improvement. 4

It is difficult to understand the relatively positive reception to the panel’s findings in some quarters and moreover, the Government’s acceptance of the findings, given that many of the major points raised for consideration for change or improvement were not implemented prior to the passage of the Safeguard Mechanism legislation, showing the government and minister Chris Bowen’s desire to seem to be doing something. The heavy reliance on carbon credits in the Safeguard Mechanism supports the move away from decarbonisation policies to offsetting.

CARBON OFFSETTING … DELAYING JUDGEMENT DAY?

Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs) are administered by the Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) under the overall supervision of the Clean Energy Regulator – an agency governed by an independent statutory authority, also known as the Clean Energy Regulator.

The ERF has two main functions – both under the banner of Australia’s carbon crediting scheme.

The first is the operation and encouragement of projects for landholders, communities and businesses that avoid and reduce the release of greenhouse gas emissions, and to encourage the removal and sequestering of carbon from the atmosphere. This could be achieved by employing new technology, by changing methods of land use and management of vegetation to facilitate carbon reduction, and by upgrading equipment, but as yet is problematic as will be discussed later.

The second function is the management and distribution of Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs) – the credits that are earned by those participating in carbon reduction methods as described above. Participants earn one ACCU for each tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent (t-CO2-e) that is stored or avoided by the particular project. The ACCUs earned can then be sold to either the government, or to private buyers. ACCUs operate in a market, overseen by the government but a market nonetheless.

In 2000 after three years of debate and wrangling, a Renewable Energy Target (RET) was legislated. Although the legislation was brought on by the Coalition under Howard’s leadership, there was reluctance to act on climate change by many in the Liberal and National parties.

After the Coalition defeat at the 2007 election previously wary coalition members became more hardened against climate change action and many publicly opposed any action in opposition. By the time the Coalition regained government under Abbott, the dye was set, and it became obvious that the conservatives in the Coalition, including their leader Abbott, were going to fight hard to try to abolish RET and give full support to existing and proposed businesses and mines that were responsible for a large proportion of Australia’s emissions. 5 & 6

Despite opposition to the RET, even from the government, as well as major problems with governance of the scheme, the targets that were revised to 45,000 GWh by 2020 were met in 2019. There was also an estimated reduction in emissions of around 300 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2-e) between 2012 and 2022. During the period from 2010 to 2019 the revised RETs encouraged investment in renewable energy projects. For non other than political reasons, after the 2020 RET target was achieved the RET scheme was not renewed or extended. 7

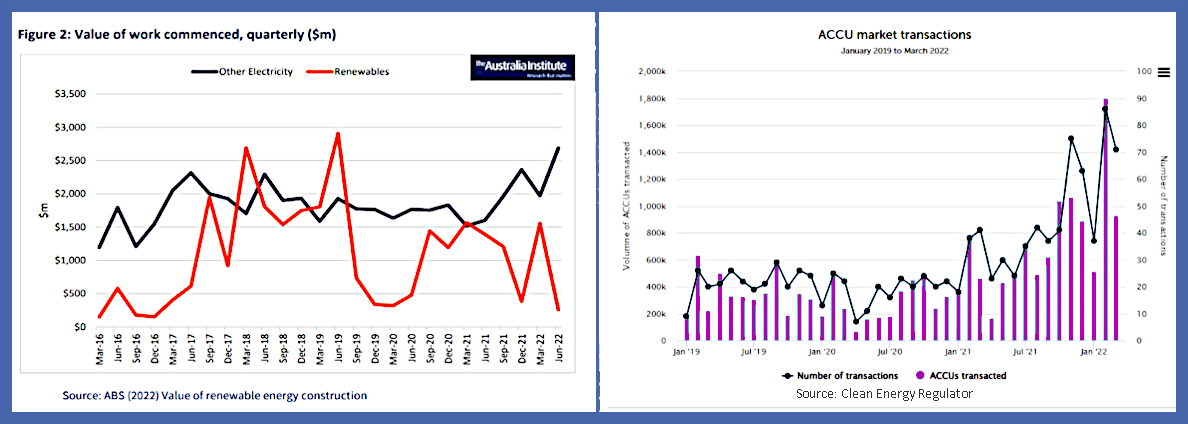

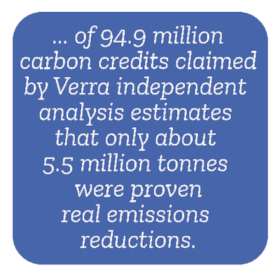

In data from the Clean Energy Regulator, ACCUs reached a new record amount of 23 million in 2022, including demand from voluntary buyers 9, eclipsing 17 million in 2021 and 16 million in 2020. Since the release of the reformed Safeguard Mechanism in March 2023 there has been an even higher demand for ACCUs in Australia. Carbon credits were to be a small cog in a big wheel helping larger carbon emitters offset some emissions in the early days of legislated emissions reduction – in Australia, carbon credits are no longer the small cog, they are the wheel, and instead of scaling down, the increase in demand and dependency for carbon credits is exponential. In stark contrast to the increase in ACCU investment and projects, construction and investment in renewables has declined since 2019, which happens to be around about the time of neglect of the Renewable Energy Target scheme (RET).

Since 2019 there has been a rapid migration of investment and funding away from renewable energy projects to carbon offset markets in Australia. Private or voluntary 8 carbon offset markets are popping up all around the world, many dealing in carbon offsets that are, at best, of questionable integrity. Australia is one of few developed countries where free use of carbon offsets have full government support as one of the mainstays of climate carbon policy.

Offsetting carbon does not actually reduce carbon it is simply a means by which a carbon emitting organisation can counter or offset their emissions buying carbon offsets offered by other projects supposedly decreasing carbon in the environment. These projects include reforestation and conservation, renewable energy, community projects and waste to energy, of which reforestation accounts for the largest proportion of carbon credits and is the one that is least accountable.

Offsets will not reduce carbon emissions. Offsets will do nothing to quell the unnatural occurrence of devastating fires, floods and droughts. Offsets will allow industries to pollute as usual. Voluntary offset markets will by their nature will always have a primary desire for financial profit with emission reduction becoming, at best, a secondary aim. Carbon offsetting should be a last resort for specialised and critical industries where emissions cannot be countered by any decarbonising processes.

One definition offers ‘carbon offsetting enables organisations to compensate for or neutralise emissions that have not yet been eliminated’. In this description, the use of a word like “neutralise” to describe emissions is highly misleading because all that is occurring is the simple transfer of carbon from one location to another; neither neutralisation nor reduction is taking place.

CARBON COWBOYS

When you pay a little extra in a levy to offset emissions on your power bill it probably makes you feel better, it might make the power company look better, but does it actually help the environment in terms of reducing carbon. Very likely not!

Concerns over the integrity of Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs) have been expressed for years due to alleged malpractice of some participants supplying the credits, and the Chubb enquiry into ACCUs has done little alleviate concerns.

Analysis of outback forest regeneration set up to store carbon and awarded millions of carbon credits worth hundreds of millions of dollars show an actual decline in tree and shrub cover. The former head of the governments Emissions Reduction Assurance Committee and environmental law professor at ANU Professor Andrew Macintosh and a group of five other academics – Dr Pablo Larraondo, Professor Don Butler, Dr Dean Ansell, Marie Waschka and Dr Megan Evans conducted the analysis, set up to illustrate the problems with forest regeneration projects. Forest regeneration either did not occur at all, or at best some regeneration was due to rainfall and would have occurred anyway. Professor Macintosh and his colleagues estimated that 165 outback projects examined received 24.50 million carbon credits yet the combined area of forest and sparse woody vegetation cover decreased by 60,000 hectares. 10

According to GreenCollar, 12 one of Australia’s largest environmental markets investor, natural resource manager and conservation-for-profit organisation, there needs to be improvement in the method of measuring the amount of carbon being drawn down from the atmosphere and stored in vegetation, as well as the governance of the ACCU system by the Clean Energy Regulator. This criticism is by one of the free market leaders and backs up that of another market leader, Fortescue’s Andrew Forrest11. It also supports at least part of the disapproval expressed by science and academics, including Professor Macintosh.

Subterfuge and lack of integrity are not realms restricted to some Australian operators. Where there is money there is corruption, as is the case in Papua New Guinea 13. An American company, NIHT Inc (New Ireland Hardwood Timber) was formed by Stephen Strauss, primarily as a timber logging company in Papua New Guinea. Strauss has an interesting and somewhat dubious corporate history having had a US court judgement against him repeatedly and knowingly and/or recklessly defrauded investors by disseminating false and misleading information in a past corporate venture.

An ABC 4-Corners investigation into Strauss found that NIHT Inc had coerced local people into signing agreements without full disclosure. He then set up an astute marketing campaign and sold millions of dollars of carbon credits around the world, including to many well-known Australian businesses including Active Super, The Sydney Opera House, the law firms Corrs Chambers Westgarth and Gilbert and Tobin, Planet Ark and Nespresso, all of whom had bought the credits in good faith and had no idea that the idyllic tropical rain forest timber storing their carbon was also being logged – not necessarily by NIHT Inc, but certainly with their knowledge. The 4 Corners program Carbon colonialism is available free on ABC iView and well worth watching. 13

Repercussions followed the airing of the 4-Corners program and HIHT Inc’s right to trade was suspended by Verra, the world’s largest carbon project verification organisation. However, sadly on 14 March 2023 Verra lifted the suspension, something that should ring alarm bells for anyone who cares about the environment and vulnerable indigenous people. It is appropriate to note that Verra’s reputation is under a cloud as an investigation has stated that more than 90% of Verra carbon offsets are worthless. 15

A nine-month investigation of Verra, undertaken by the German weekly Die Zeit, SourceMateria and the Guardian, has uncovered the astonishing fact that over 90% of rainforest carbon offsets by the world’s biggest certifier are worthless.14 The studies found that very few of Verra’s rainforest projects showed evidence of deforestation reductions, and that threats to forests had been overstated by on average 400% for Verra projects. The rainforest offsets had been bought by many internationally known identities including Shell, Gucci, Disney, Salesforce and the band Pearl Jam. Verra argues that the conclusions reached by the studies are incorrect, and questions methodologies used, however even if the investigative studies were slightly inaccurate, the fact is that of 94.9 million carbon credits claimed by Verra independent analysis estimates that only about 5.5 million were proven real emissions reductions.

A nine-month investigation of Verra, undertaken by the German weekly Die Zeit, SourceMateria and the Guardian, has uncovered the astonishing fact that over 90% of rainforest carbon offsets by the world’s biggest certifier are worthless.14 The studies found that very few of Verra’s rainforest projects showed evidence of deforestation reductions, and that threats to forests had been overstated by on average 400% for Verra projects. The rainforest offsets had been bought by many internationally known identities including Shell, Gucci, Disney, Salesforce and the band Pearl Jam. Verra argues that the conclusions reached by the studies are incorrect, and questions methodologies used, however even if the investigative studies were slightly inaccurate, the fact is that for 94.9 million carbon credits claimed by Verra whereas independent analysis estimates that only about 5.5 million were proven real emissions reductions.

Last month Kenya hosted what is so far the world’s largest auction sale of carbon credits. Buyers of most, if not all, of the 2.2 million tonnes of credits were unsurprisingly, Saudi Arabian companies including Aramco, Saudi Electricity Company and Saudi Airlines who paid an average of $US6.27 per metric tonne. The organiser of the Kenyan auction was also a Saudi identity – Regional Voluntary Carbon Market Company (RVCMC) founded by the Saudi Public Investment Fund and Saudi Tawadul Group. RVCMC will be setting up a full-time carbon credit exchange in the Saudi capital Riyadh in 2024.15 This is something we should all be very concerned about as the country that has historically supplied more oil to the world moves into a market place to profit from ‘hiding’ carbon. The immense wealth of Saudi Arabia could do so much in helping develop technologies to reduce and eliminate carbon, not hide it.

NET ZERO … ALMOST OUT OF REACH

Australia’s reluctance to do much more than ‘mark time’ on climate change action for the past ten years would almost rule out relying on either carbon capture and storage or green hydrogen to help reach anywhere near the 2030 target, as neither of these technologies have shown consistent nor reliable results in reducing carbon, despite multi billion dollars being spent.

Carbon capture and storage was much touted by the mining industry and former Coalition minister Angus Taylor to remove carbon as part of the so-called “clean coal” technology. At Chevron’s Gorgon gas facility on Barrow Island, which was the world’s largest carbon capture ans storage project, instead of carbon emissions being reduced, emissions have risen almost consistently since 2016. Carbon capture and storage is not working and taxpayer subsidies are being wasted.

Green hydrogen has shown promise as a future clean, renewable fuel source, and despite the hype, has not yet delivered. Hydrogen is plentiful but exists mostly in molecules bound to other elements, from which it must be extracted and the energy cost of extraction is greater than the energy that can be derived from the extracted hydrogen. Green hydrogen technology should continue to be researched and trialled, the urgency of a need for reliable and clean renewable energy as a stopgap measure would rule out green hydrogen for the very near future.

The continuing widespread use of carbon credits and the prevalence of carbon markets as the main source of carbon credits will almost certainly ensure that the forecast emission reduction targets for 2030 and 2050 will not be reached. Trading in carbon credits will not only provide a haven for profiteers at great cost to the environment, but will also make emissions reduction much more difficult as climate-caused natural disasters become more and more common.

There is no absolute certainty of longevity or security that the artificially sequestered carbon being stored in various ways will remain undisturbed in situ, even in forests that can be logged or cleared for intensive agriculture if not properly governed.

If we were to stop adding extra CO₂ to the atmosphere today and take no other remedial action, it would still take centuries for bio systems such as photosynthesis to bring the CO₂ levels back to the pre-industrial average levels.

Desertification has been described as the greatest environmental challenge of our time and climate change is making it worse. It could also be argued in reverse, that desertification is making climate change more rapid! Today there is only about 50% of vegetation on the earth’s surface as there was 10,000 years ago thereby drastically reducing the ability of photosynthesis to naturally sequester atmospheric carbon into the soil. Tie this in with denuding of soils due to bad agricultural practices and climate warming causing more and more desertification of the earth’s surface and there is an almost perfect scenario for the advancement of global warming – and all happening in the very medium that could and should be the earth’s saviour, the soil.

Improving soil health and profiles adds to the capacity of the soil to acquire carbon and for every gram of carbon put into the soil there is a huge increase in the water-holding capacity of the soil, creation of well-structured 3-D soils, an increase in surface area exposure of minerals in the soil, and an increase in the bio-fertility of the soil.

Not only does natural carbon sequestration to soil and stable vegetation reduce carbon from the atmosphere, but the improved carbon content in the soil increases vegetation growth and water retention also reduces greenhouse radiation, thereby helping cool the atmosphere.

Three new coal mines that have been approved since May 2022 (when Labor was elected government) will mine 44 million tonnes of coal with total emissions of 116 million tonnes. There are at least 25 additional proposed coal mines waiting for approval which, if approved and added to those already approved, would contribute 12.6 BILLION tonnes16 of emissions over the life of the mines – great for government coffers, but a disaster for Australia and the world. Delinquent and irresponsible decisions like this are made without conscience and would ensure a warmer, drier more barren Australia, the end of the Great Barrier Reef, and no possible way of ever reaching net zero emissions. As well as making a better effort at reducing our own carbon emissions, perhaps Australia should start bearing some responsibility for emissions from the coal and gas we export.

New essays on the role of soils and the ocean in the war on climate change will be available later this year.

References

1. Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water – Safeguard Mechanism Reforms – May 2023

Extract from National Grid website

Scope 1 covers emissions from sources that an organisation owns or controls directly – for example from burning fuel in our fleet of vehicles (if they’re not electrically-powered). | Scope 2 are emissions that a company causes indirectly when the energy it purchases and uses is produced. For example, for our electric fleet vehicles the emissions from the generation of the electricity they’re powered by would fall into this category. | Scope 3 encompasses emissions that are not produced by the company itself, and not the result of activities from assets owned or controlled by them, but by those that it’s indirectly responsible for, up and down its value chain. An example of this is when we buy, use and dispose of products from suppliers. Scope 3 emissions include all sources not within the scope 1 and 2 boundaries.

2. Environmental Defenders Office – Safeguard MechaniSafeguard Mechanism reforms – another significant step in Australia’s climate law renaissance by Frances Medlock, Commonwealth & Government Liaison Solicitor

3. The Guardian, Mostafa Rachwain, Natasha May & Rafqa Touma – Concerns over use of’cheap and easy’ offsets | Jan-2023

4, ACF – Carbon offset limits | Australia and Kazakhstan top the charts | Feb-2023

5. There is a complex web of government bodies administering Australia’s multi-layered emission reduction programs, including the ministries of Climate Change and Energy, Environment and Water, Resources, Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Industry and Science. Within the Department of Climate Change and Energy are most of the bodies mentioned in this essay, including: the Clean Energy Regulator, a non-corporate Commonwealth entity as well as an independent statutory authority; the Emissions Reduction Fund, a voluntary scheme under the auspices of the Clean Energy Regulator, responsible for the crediting, purchasing and disbursement of carbon credits or ACCUs,

6, S&P Global – Commodity Insights | May-2023

7. Article by Adam Morton | Climate and environment editor | The Guardian

8. The Australia Institute | The Problem with Carbon Credits and Offsets Explained | Feb-2023

9. Article by Adam Morton | Climate and environment editor | The Guardian 10-Oct-2022

10. Article by Fiona Harvey | Environment editor | The Guardian 22-Sep-2022

11. Climate Council | What is carbon capture and storage | 8-Feb-2023

12. Australian Financial Review, Jacob Greber Carbon market player Greencollar agrees ACCUs have integrity problems | Oct-2022

13. ABC 4 Corners | Carbon Colonialism | 14-Feb-2023 | Watch on iView

14. Petya Trandafilova, Carbon Herald | The Guardian Investigation Of Verra Carbon Offsets Claims More Than 90% Are “Worthless” | 21-Jan-2023

15. Reuters | Saudi companies buy 2.2 mln tonnes of carbon credits in Kenya auction | 15-Jun-2023

16. The Australia Institute: Coal Mine Tracker | Jun-2023